Maybe.

If you want to know what it looks like to learn using Engelmann’s techniques, take 45 min and watch this.

At age 9 I desperately wanted to learn French, tried with a few language tapes, and failed.

At 10 I tried again. It all seemed to be going great, but then I realised I was getting stuck at the same point as before – le, la, les. How can there be three words for ‘the’!? I failed again.

And so it was with great enthusiasm and excitement that I looked forward to studying French at school, age 11.

I failed, again.

Slowly, and systematically, my attitude in French lessons deteriorated over 5 years until I would say things like ‘What’s the point in learning French anyway, everyone speaks English!’

My French GCSE grade was a D, it was the only grade that wasn’t an A or A*, and by that point I didn’t care.

Six months later, free of school, my old passion returned. For the next six years I will again want to learn French, but my attempts to join classes at Warwick failed.

When I finally graduated, I moved to France, and got lucky: a friend recommended Michel Thomas’ CDs to me.

In one month I learnt more French than I learnt in five years at school.

I described it as effortless. As I took an interest in education, I turned to Michel Thomas as one of my influences. I could see some of the things he was doing… one of my friends failed completely with the CDs and gave up quickly. Why? He kept repeating the first CD, trying to ‘memorise’ it – exactly what Thomas forbade.

I just ploughed onwards, as he asked, and I discovered something interesting: just as I realised I’d forgotten how to say something, like ‘glass,’ a moment later he would ask something like ‘How would you say I would like a glass of red wine, in French?’ You’d have to sit and think long and hard to try to remember that word you felt you’d just forgotten. If you couldn’t recall it, hit play, and bam! Verre. That’s it! You didn’t forget it again for a long time (10 years and counting, in my case.)

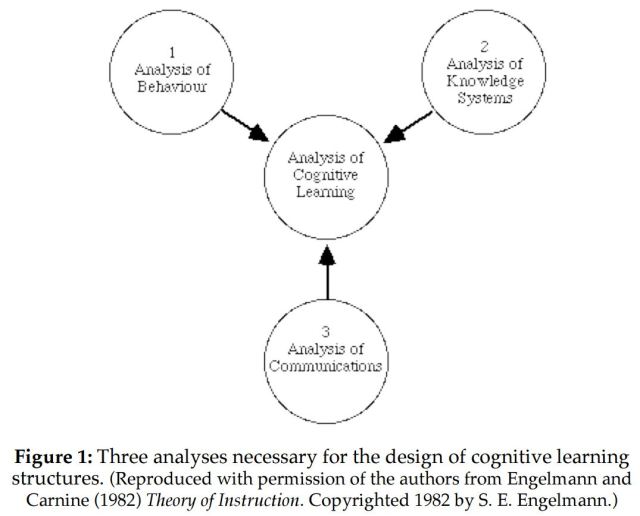

Engelmann’s Theory of Instruction (1982) has three essential parts:

- Analysis of knowledge

- Analysis of communication

- Analysis of behaviour

31:10 in the documentary:

“It takes Michel eight months to dissect the complete structure of a language…”

That’s analysis of knowledge.

“…and find a way to teach it so that it is effortless to learn.”

That’s analysis of communication.

“Like, when he talks to you and asks you a question, it’s like he’s looking into you and knows that you’re thinking inside.”

That’s analysis of behaviour.

Thomas’ experience meant he knew the misconceptions and the mistakes that learners would always make, knew the behaviours they would exhibit, and accept and correct accordingly. In Engelmann’s Theory, behavioural analysis is about watching to see how learners respond following instruction and adapting as appropriate. It’s the practice of being a classroom practitioner, what most of us have learnt as ‘questioning’ or AFL. Thomas was so preternaturally good at this that when he attempted to engage universities in the US they insisted that there was no ‘master method,’ and pointed to Thomas’ natural charm and charisma as the secret to his success during his late 60s experiments in LA schools. In other words, they retreated right back to decades-old theories of ‘the natural born teacher,’ (which I’ll be discussing at ResearchED this weekend.)

But it wasn’t anything so mystical, he just knew the structure of the language, knew how he was trying to communicate it, knew where it might go wrong, and knew what to do about it. It was knowledge, derived from experience.

This is about the same time in history that Engelmann was developing his Theory of Instruction with Doug Carnine.

“…and interestingly one of the girls said: After five years in school, my French teacher, she said ‘I think you better give up because there’s no way you’re going to succeed.’

And here she said: I just managed it! Fine! I feel as though I understand it!”

I don’t know if it’s possible to make all learning effortless, but I do know that we can do a lot better than we’re doing.

When this documentary was filmed, it was true that we didn’t know how Michel Thomas’ method worked. Although tapes of his programme existed, they could only be listened to inside his schools.

This is no longer the case. The recorded programmes are publicly available. They have been analysed, and the former secrets of his method are laid bare in Prof. Jonathan Solity’s book The Learning Revolution. Sadly, like Engelmann’s Theory of Instruction, this book is now out of print, and sells for exorbitant amounts on the Amazon marketplace. In it, you will find many of the tricks that are increasingly working their way into a certain part of the educational psyche:

- The 80:20 principle

- Distributed practice

- Interleaving

- The testing effect

It was in this book that I first heard about Engelmann and Carnine, and their work. They and Thomas hit upon the same set of methods independently of one another. Thomas discovered his methods empirically – trial after trial after trial, experimenting on wealthy customers.

Engelmann and Carnine combined psychology, logical analysis and empiricism to produce a comprehensive and fundamental model of interrelated instructional theory that all teachers should know.

“…the mastery of part of the language is the thing that keeps them going, and keeps them enthusiastic… and we lose site of that! In the way we teach, we think we capture their interest by finding them interesting materials that are supposedly related to their interests in the outside world, and maybe we miss the point, and I think he’s probably onto something very important here.”

That was said in 1997.

It’s been nearly 20 years.

It’s time we stopped messing around, started paying attention, and get this right.

I first encountered Michel Thomas’ French course when a friend of mine used it upon moving to France. I remember driving to work listening to it and learning more French grammar, especially, in a few weeks than I’d have learnt had I taken A-level. I was so impressed I got the German one too, having never studied any German. I found it quite inspiring! It’s particularly interesting that we can now start to explain in increasingly familiar terms why the method works so very well. You’ve made some very clear points here, Kris.

Since then I’ve always tried to approach my lessons like that: how can I demonstrate this clearly, what examples would be *most* efficient and how can I incorporate something we’ve done before? It sounds like common sense, but how many maths teachers spend their time on this line of thought rather than making a colourful resource? I have met many for whom it’s all about the Powerpoint.

One challenge that strikes me immediately is how/where to develop concrete examples (for mathematics) so that others can see how to employ the method and follow the rationale without having to go through the prolonged voyage of discovery that others of us have been on, and this is particularly important given the varied nature of ITE nowadays.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Pingback: The secrets of language learning | Improving Teaching

Pingback: The Blogosphere in 2016: Roaring Tigers, Hidden Dragons | Pragmatic Education

Pingback: The 80:20 Principle – 5 – Mental Models for Education | …to the real.

Pingback: Exam and Curriculum Change: What's the latest? - Teacher Tapp : Ask · Answer · Learn