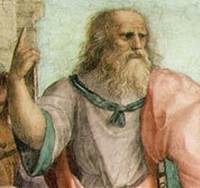

Said Plato.

So how does one become a philosopher? By having ones soul drawn ‘from the changing, to the real.’

So what curriculum is best suited to draw ones soul from the changing, to the real? ‘Why, it’s mathematics.’

By studying mathematics, Plato believed we could become philosophers, ‘thinkers’

I entered teaching through the Teach First programme, in 2011. Here are some facts:

- Over one fifth of people leave school functionally innumerate (2010): http://www.tes.co.uk/article.aspx?storycode=6042996

- Below two thirds of people achieve a C grade in mathematics, while less than a third reach a B (2012): http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/datablog/2012/aug/23/gcse-results-2012-exam-breakdown#data

Here’s what I believe:

- Achieving a C grade on the current exam papers requires very little mathematical ability or understanding

- Almost 100% of the population are intellectually capable of achieving an A* on the current papers, if the correct systems, curriculum and pedagogy are in place

I know there are already people who’ve figured out how to run the most effective schools in the toughest circumstances, though given that, I don’t yet understand why all our schools are not equally effective.

I know that others have figured out how to design the most effective curricula, though I’ve yet to see their ideas applied to mathematics.

I know that others have figured out the best ways of instructing students, yet I see a persistent ideological battle being fought at this level.

Can we do better?

At least, I want to see a future where almost every child entering our schools leaves them capable of achieving what today we consider to be an ‘A*’ in mathematics.

Ideally, I want to see them capable of more.

And be literate – it’s not difficult if powers that be understand there’s a Code and some children will take more time, more practice – but ‘labelling’ seems de rigour – lots of money in this. Literatate and numerate….too many vested interests pulling the other way or ignoring 20% of children.

Literate, absolutely. Maths is what I know, though. For now.

Hi there,

I work for the Edge Foundation and have a press release that might be of interest to you with regards to the VQ Day Awards 2014 and their new Teacher Award.

Drop me and email and I’ll send it over to you!

Thanks,

Charlotte

charlotte@tinmancomms.com

Hi Kris,

I started reading Explicit & Direct Instruction in preparation for training with TeachFirst in September and had a question regarding your chapter about Project Follow Through and evidence for/against inquiry-based learning.

The evidence of DI is obviously somewhat conclusive, however, it also suggests there is a “sweet spot” that combines teacher-directed instruction in most to all classes with inquiry-based learning in some, and that this achieves better results than solely teaching via a DI approach.

My impression is that inquiry-based work might be best once student mastery has been achieved but it seems to be brushed over and curious whether you think there is a place for the inquiry-based approach in the classroom and when it works best?

Thanks,

Paul

Hey Paul.

In short, yes, I do think it has a role to play.

It feels ‘brushed over’ because the prevailing sentiment always seems to favour it, we need to do a lot yet to educate people about *effective* DI principles, and I’m betting that’s where the 80:20 gains lie.

I think if you go in trying to absolutely nail DI practices, you’ll probably get a lot closer to your goals than if you try to ‘balance’ the two (though you can learn a lot from trying stuff out and seeing what it looks like when it fails.)

I’m a little into Unit 1 Session 2 of this:

https://www.structuringinquiry.com/math-minds-online-course-launch-page/

Which explicitly argues it’s *not* trying to be a’balance’ of two approaches. Everything I’ve seen so far is excellent imo, though as I say I haven’t been through it all yet. It might be worth a look if you’re preparing for September though?

Let me know if you’d like to discuss more.

Kris,

My name is Beau. I’m a Canadian music instructor. I’m enjoying your content after following Englemann’s internet trail.

Just as you mention on your podcast with Mr. Barton, Cognitive Load Theory is revolutionary for teachers steeped in the constructivist attitude. However, Cog Load leaves the teacher no practical steps for how to design the instruction communication itself in a systematic way. Designing programs that ensure proper sequencing is also left out of these Cognitive Science – all we’re left with is that sequencing is good – but as Englemann points out, to teach and to design a curriculum are two entirely separate activities.

Looking back I can actually remember a fantastic maths teacher I had in high school who used transformations constantly – I wonder if he even knew what they were called.

The realm of music instruction has withered away worse than maths or english literacy in schools. Even while taking private music lessons. Many students only get 1/1 instruction with a knowledgeable teacher-musician for 30-60mins a week.

The arts remain even more exposed to this model of “kids learn best when they discover things” because there is always a back up clause that says, “well we’re doing this for fun, so that means it should be approached chaotically or at whim.” However, in my experience, when instruction is properly sequence into micro mastery DI style teaching – motivation and efficacy rise so fast that there really is no “tyranny” in systematic instruction as I feel many people fear there is.

Are you aware of any systems of music instruction that have taken the principles of Theory of Instruction to account?

Keep up the good work, looking forward to more from you.

Beau Taillefer

Hi Beau,

Thank you for getting in touch, I read your comment with real interest! And I’m glad what I’ve written here has been of some help. I haven’t added new posts in a while, but am slowly chipping away at a book… one day maybe it will be released.

On music, coincidentally I just bought a digital piano in August, and yesterday received the results from my Grade 1 exam (Distinction!) I’ve never played before, but have found that between the principles of cognitive science, Direct Instruction, a reasonably well sequenced curriculum in the ABRSM Grade system, a lot of YouTube, and a little help from a local tutor (5 hours,) I’ve been able to learn what feels like a tremendous amount in a very short time.

So I’m not aware of anything that’s been created like this, but I’m certain it’s possible, if it hasn’t been done already!

I secretly hope that we’ll create something like this at Up Learn one day.

Kris,

I was pleasantly surprised to see a reply. Congratulations on your recent Grade 1 exam success. I have no doubt a systematic thinker like you could achieve big gains in short periods.

An experiment I’ve been running on my students lately, which you may be interested in:

Attempt to spend the majority of your time playing in one key. Perhaps C major and A minor. Common advice has relatively novice pupils playing in many keys early on. This simply moves things along too quickly before mastery and complex relational features within a key become obvious to the student.

Based on Chapter IV – Programs, in Theory of Instruction, it would be easier to develop a rich melodic and harmonic vocabulary in a single key, and then use DI principles to translate these ideas into multiple keys – if that is indeed your aim.

For example, many students will learn a I – V in several keys. This time would be better spent learning more harmonic vocabulary in a single key. Usually the time spent to learn a I – V in three keys could be better spent learning to play i – V – v – iv – IV – Vi – etc in an original key.

This also creates a situation where every song you learn becomes a juxtaposition of relationships between every other song you learn, without imposing a mental challenge onto it. Simply asking a student to play one song and then another produces a juxtaposition.

The most common criticism I’ve seen to this method is “Well sure you’ll get quick results but playing in all keys is hard – and hard is good” It’s remarkable how common this mindset of “hard is good” is. This goes against the Englemann idea of 70-90% success rate for new material.

Please do keep in touch and reach out by email, I would love to have a chat about all things music, life and education if you’re ever open to a fun afternoon.

– Beau