This one’s somewhat lengthy. Given the complexity of the issue, I really can’t make the post any shorter, and I think splitting it into parts would also confuse its message. Hopefully it’s worth the read!

***

Recently I published this, in response to this.

It sparked a little debate on twitter, and in one rare and exciting moment I found myself agreeing with Debra Kidd and disagreeing with Old Andrew!

Read from bottom to top:

The issue was around the pedagogical idea of practice, and essentially the value-driven ideas of whether or not school/learning should resemble fun, or hard work.

Here I hope to add in some of the nuance to what I said on Twitter.

Mastery

First some caveats. I’m going to help myself liberally to words such as mastery, mastering and mastered. As I do, the reader should be aware that I’m using the terms colloquially, as anyone might understand them, and not as they might appertain to a ‘mastery curriculum.’ When used in that context, ‘mastery curriculum’ should speak to specific design choices of the curriculum, rather than just the sense that learners should learn things… everyone thinks that learners should be learning what we try to teach them.

Next caveat, I need to make explicit what aspect of mathematics instruction I am referring to. Learning how to conduct a mathematical investigation is different to learning how to solve complex problems, which is different from learning how to apply standard procedures, which is different from learning something conceptual, which is different from learning something factual. A child could practice running investigations, for example, but you certainly couldn’t make use of drill practice for learning about how to conduct investigations! So I’m sticking to mathematical knowledge or skill that can be developed through drilling specifically, for example arithmetic, or basic expansion of brackets.

Possibilities

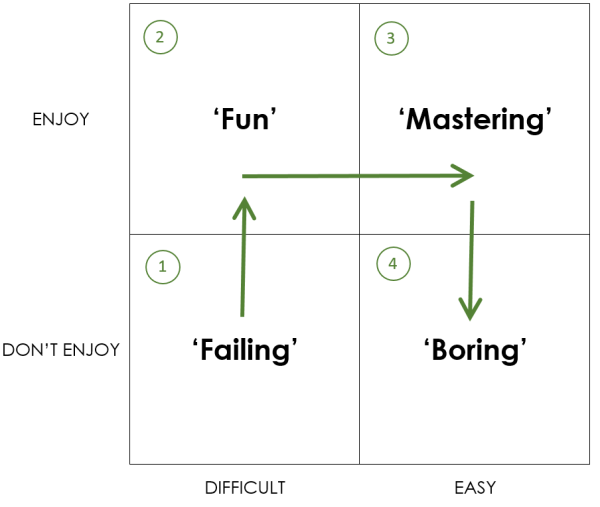

There are four broad and likely scenarios in the classroom:

- Pupils try to practice, find it difficult, don’t enjoy it

- Pupils try to practice, find it difficult, enjoy it due to the classroom context

- Pupils practice, find it easy, enjoy the feeling of success and progression

- Pupils practice, find it easy, find it boring and tedious

You could map them out like this:

Accounting for the scenarios

Thinking a little about how these four scenarios might come about:

In scenario 1, pupils are simply failing; they cannot reproduce what the teacher is doing. This can happen for many different reasons, but suffice it to say that no learning and no success is taking place (anything that can be drilled is unlikely to be an activity where ‘being stuck’ or struggling is a desirable feature of the learning process, whereas that could be the case for problem solving, for example.)

In scenario 2 the pupils may be succeeding, or they may still be struggling, but either way the teacher has done something to the classroom environment to make the experience a fun one nonetheless. Once again, Bruno’s Times Table Rock Stars is an exemplar of this in action.

In scenario 3, there may be no such trappings, but pupils who have not yet ‘mastered’ the procedure are benefiting from the sense that they are improving in its application as a result of the practice. They are delivering answers with increasing speed, the whole process is becoming easier to apply, more fluent. The desire to improve further is spurred on by the satisfaction and sense of achievement gained from palpable progress.

In scenario 4 pupils may have genuinely mastered the content. For all intents and purposes this is equivalent to asking a maths teacher to sit down and add up all the numbers from 1 to 100. Why? We know we could do it, but it would be boring, and tedious; like ironing – to borrow Debra’s example – we’d rather be doing something more interesting with our time.

To be clear, such pupils will still need to practice whatever procedure or technique it is from time to time, but drilling in particular would have lost its utility, and hopefully the practice could come instead from interleaving (embedding the mastered procedure as a small step of a more advanced procedure to be practiced e.g. multiplying fractions stills leads to the practice of times table multiplication.)

Paths to Mastery

As I use the word ‘mastery’ here, I have a sense of someone who essentially has ‘teacher-like’ levels of facility in, say, expanding brackets, manipulating numbers in index form, simplifying surds etc. Is that a feature of a ‘mastery curriculum’? Maybe, maybe not, I’m not using the word in that context, I’m just trying to picture the individual who would find drills of a certain activity tedious.

Everyone starts out unable to do things such as those described above, until they are taught, and they practice. Here are three possible paths they can go on, I imagine:

Path 1 – ‘Straight Forward’:

A straight-forward case in which a teacher models a process, pupils replicate it, practice it, improve, are motivated to do so, and then finally master it. Further drill practice would become redundant and be classified by the pupils as ‘boring.’

Path 2 – ‘Pre-emptive’:

A pre-emptive case in which a teacher either suspects some pupils will lack initial success or motivation, and so finds a context in which to inject additional joy into the classroom until the pupils are at a point where they can derive satisfaction from the work itself.

Path 3 – ‘Adaptive’:

An adaptive case in which a teacher recognises that a disengaged pupil body are failing to grasp and replicate the process, and so the teacher adapts by finding a way of rallying morale so that pupils begin to engage and practice until, again, they start to derive enjoyment from the practice itself.

Even here, so much nuance is left out. ‘Easy’ when mastering does not mean the same thing as ‘easy’ once mastered. Whether a task is ‘easy’ or ‘difficult’ is a continuum, not a binary position.

Novice-Expert Continuum

This relates to the idea that the way in which a person learns best can change as they progress from being a novice to being an expert. They are not an ‘expert in everything,’ just in the particular thing that they are learning. In Debra’s original post she mentioned that the class in question were a top set. Children who find themselves in top sets also tend to exhibit ‘expert like qualities’ in my experience/opinion when compared to their peers. When talking about mastering procedures, this would mean that they tend to always take the top path I outlined, and that they walk it much faster than those around them, arriving at mastery much quicker, and therefore boredom when encountering further drills on the same topic. If true, this would explain the particular reactions to the experiment’s questions.

Misunderstanding

Without a comprehensive overview of types of mathematical content and activity, and without an overview of how pupils can come to engage with those different contents and activities, I suspect it can be all too easy for wires to become crossed and for people to misunderstand one another.

For example, when Debra spoke of the need for more investigations, I suspect she was overlooking the role played by procedures and procedural practice in mathematical development, treating investigations as ‘equivalent and better’ rather than ‘different and different.’ I also suspect that Debra was picturing children mostly in the bottom-right quadrant, whilst being unaware of children in the top two possible quadrants.

When Andrew spoke, I suspect he had the children in the top-right quadrant in mind, while ignoring the reality of the bottom-right. I also think the idea of ‘flow’ was perhaps being misapplied… I’ve not read Csikszentmihalyi’s book, but the sense I pick up is that ‘flow’ relates more to facility with cognitively interesting or physically challenging activities, rather than just crunching through the mundane (correct me please if you know better and I have that wrong.) Maybe a person could experience flow if they were in the top-right quadrant; experiencing challenge, but one over which they were gaining increasing facility. I don’t believe that flow would be experienced in the bottom-right; nothing flowy about adding up all the numbers from 1 to 100 (Gauss’ coup de prof aside…)

Concerns

Everyone wants the same outcomes from education, more or less. There is no doubt disagreement as to how best to achieve those same outcomes, and so when one person says something that appears it might damage the experience of children in schools, or the experiences of their future selves, we naturally fear that what was said becomes a message of influence.

When Debra says that ‘perhaps we need a little more mystery and a little less mastery,’ my concern, and I expect Andrew’s, is that the necessity of drill practice is being overlooked, and the existence of pupils who can enjoy drill through the efforts of the teacher, and those who enjoy it due to feelings of progress and success, are being ignored. A distorted picture of reality is presented to the reader, in combination with a dangerous message.

A distorted reality

Andrew essentially suggested that all pupils will enjoy drill practice once they have mastered a topic. Therefore, if they don’t enjoy the work it will be because they haven’t yet mastered it. The role of teacher then is not to make things fluffy and fun, but rather to remain stalwart and encourage pupils to practice until they achieve top-right nirvana. But, this too ignores the realities of the top-left and bottom-right quadrants.

An equally distorted picture?

I share Debra’s concerns here that pupils who find themselves in the bottom right would go on to be drilled in pointless and mundane topics when there is a more useful, interesting and efficient way for that time to be spent. I share Debra’s concerns regarding children leaving school having only negative experiences of mathematics; this is something we must take seriously, and work to address. But Debra was missing the experiences of the top-left and top-right; she concluded that ‘drill must be bad, and other activities good,’ rather than acknowledging that there are contexts in which repetitive drill can be an enjoyable activity, as well as a necessary one. Which takes us back to Andrew’s concerns, that Debra represents a group who would eliminate necessary activities and replace them with ‘fun’ ones in which less learning took place, so really we just need to toughen up and accept that not all learning is fun and push pupils until they master content, but that misses the point that sometimes repetition of mastered content is truly boring and unnecessary, which takes us back to… you can start to see why we argue ourselves round in circles sometimes; lack of communication and misunderstanding have as much to do with it as ideological differences.

When people argue that school should be fun, the concerns that people like Old Andrew and I have is that necessary activities are being replaced by ones that are more fun and from which pupils learn less. The extreme straw man is of course to point out that we could easily make school fun by replacing all learning with endless game playing. I remain in two minds as to whether or not there are people out there whose views are truly represented by this extreme position… I suspect that most believe that the learning can occur, and will even better occur, through ‘fun’ activities, rather than believing that fun and happiness are important and learning isn’t. This now becomes a valid pedagogical battleground – “Pupils will learn more through X rather than Y” is a hypothesis that can be subjected to empirical scrutiny.

When people like Old Andrew and I argue that not all learning can be fun, that hard work and, yes, even grit or resilience are sometimes necessary, I suspect that people who share Debra’s views fear we imagine a school with conditions similar to a Victorian workhouse, in which children are subjected to endless authoritarian oppression in the name of churning out carbon-copies of young adults who can spout facts and quote poetry but do no real thinking for themselves; again, another obvious straw man.

Conclusion

I need to tidy this up.

Sometimes the work necessary to learn just isn’t fun, or enjoyable. Sometimes it is just real, genuine hard work. Sometimes trying to pretend otherwise risks being disingenuous, and disadvantaging children in school. I would liken it to someone who just wants to play a game of tennis instead finding themselves having to practice serve, after serve, after serve, on their own, trying to improve that one facet of their game. That can’t be that much fun after an hour or two, surely? Yet you can’t pretend that it’s possible to get better at tennis without practice.

Sometimes the work necessary to learn just is enjoyable. No worries here.

Sometimes the work necessary to learn isn’t enjoyable, but can be made to be without any detriment to learning. If this is possible, who would to prevent it?! This was probably where I started, pre-teaching. I was mostly focussed on theories of gamification, such as those espoused by Jane McGonigal. It wasn’t until I realised how many ‘quick wins’ there are to improving how much a person can learn in school, and just how much motivation and enjoyment can come from those feelings of success alone, that I shifted focus; I do still take an interest in ideas such as these, though.

Finally sometimes the work isn’t enjoyable and that’s because we’ve made the wrong choice, and are giving the wrong work to the wrong pupils at the wrong time. We would need to acknowledge this and readjust our plans accordingly. It might be too difficult (failing) or it might be too easy (boring). Debra was right in my opinion when she said that this was an issue of high expectations – it’s a related issue, at least.

I suppose the final question is to ask what the priority for schooling should be, if asked only to choose between enjoyment, and learning. I will always prioritise learning first, and I think to do otherwise is to fail our student charges. I will always remain sensitive to the importance that a person’s school experience be an enjoyable one, as well. Once the process of and actions that lead to learning are understood, I would then turn my attention to the experience second.

I get the feeling that some people naturally start from a position of joy and happiness, and then consider learning second… but then I wonder how many, if any would openly admit to that.

I think the one point I’m making that you may not have picked up on is that when you are sufficiently fluent then a previously dull task can be so utterly effortless that it doesn’t seem dull and might actually feel relaxing. It may cease to be of any educational use to do the activity at this point, but it is not dull. When practising times tables, the ones that can do 100 questions in 3 minutes are often less bored than the ones that take 6 minutes, even though they are probably thinking less. We get bored when we are thinking dull thoughts, rather than when we are not thinking at all. Often we enjoy what we can do automatically.

But how true is that, or, to what extent is it true?

In my mind I was addressing it with the example of the adding up the numbers from 1 to 100. I’d be pretty bored by that.

Likewise there might be times when I’d appreciate a bit of renewed quick practice with the times tables, but if someone *forced* me to be repeatedly doing them every day, then I would both be quickly bored by it and grow to resent the person making me do it.

I wouldn’t be. I find times tables relaxing. I wouldn’t want to do them for an hour, but 100 questions is really no effort and wouldn’t take long enough to get bored by. I don’t know how common this is, but when I encounter kids who are unlikely to ever get faster that is usually what they are like. The “I’m bored” kids are usually ones who could still make further improvement.

Would they be happy doing it every day though? I suspect they wouldn’t; my highest achievers were growing increasingly restless with various rapid fire drills we did last year, as they progressed.

Either way, I think it’s a reality that can’t be denied, that some people can reach a point of mastery and not find it that much fun to continue practice drills; and why would we want them to, anyway? Surely we’d want them to be moving on to other things by that point.

My two cents as a 11th grader: This is very true. Often times i used to be so bound by the curriculum and the fear of doing each and every sum rather than choosing variety, it made it comforting to drill the same type of exercises over and over again because i was not struggling. It only helped me score good marks in school exams, but i wasnt being tested on my problem solving skills i was being tested on how well i know the book. Initially its important to do some drilling exercises if a topic feels unfamiliar(Obviously after understanding it thoroughly)but after a while we should pick variety over repition.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Depends on the drill, and perhaps that’s what I need to consider here. But I have frequently been caught out by the tolerance high ability kids have for routine calculations. It doesn’t mean they learn from them, but I am far from convinced that boredom, or even the maximum level of boredom, coincides with the point where there are no further gains to be made. I’ve done drills where the most able are content and those who could still improve are bored.

Reblogged this on awareyetpensive and commented:

Really like this blogger – lots of what he says oozes common sense!

I think that Debra Kidd is guilty of more than a little confirmation bias in what she is saying as it does suit her point of view. In addition, none of us were in the room and we don’t know how leading the questions were. Often children do say what they think they adult wants to hear and if they are sensing that she was open to their moaning then no doubt would have focused on it.

I imagine a lot of children are sick of both reading, writing and maths after SATs – the fact that it is a whole year of very little else other than making sure everyone gets at least a Level 4 means that many of the high ability are probably not being challenged. No doubt stressed out Year 6 teachers are repeating things for the sake of it to be sure and not be caught out. It says more about Year 6 than maths in my opinion.

I agree that we have to look at why the child may be bored – accepting a range of possibilities not jumping automatically to either the child’s lazy or the task is not engaging enough (this might be the case but it might also be they struggle with one times table more than others say).

Teachers who want to make learning fun are more guilty of shoehorning objectives to the ‘fun’ task. This does promote low not high expectations. While starting with the objective and the high standards is essential – it is however possible to make this fun – I have no problem with the children singing times tables songs if it helps but mix this up with tests.

Pingback: Why Do I struggle Learning to Code? – thatsgrandblog