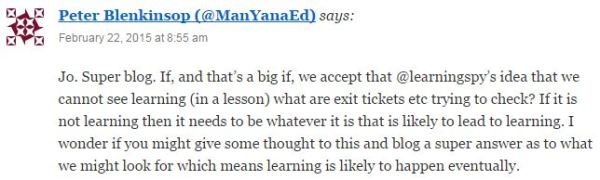

Earlier today Peter Blenkinsop left a comment on this post by Joe Kirby, making a very good point.

He’s referring to the work that David Didau’s been doing over the past year to try to explain how ‘learning’ isn’t a thing that necessarily happens in one lesson. It might, but it might not, and in that lesson we have no way of knowing.

From this, Didau has been making the point that a lot of the rhetoric around ‘sustained and rapid progress’ in lessons, or around ‘mini-plenaries to show observers what marvellous learning is taking place,’ or even that the entire graded observation machine and the cult-of-outstanding are deeply flawed.

So, if all that’s true, if learning cannot be observed in a lesson, what on Earth is the point of AfL assessment mechanisms such as exit tickets, and for that matter, hinge questions, mini-whiteboards, checking kids’ work as they’re doing it, any kind of marking, and anything else you might dream up!?

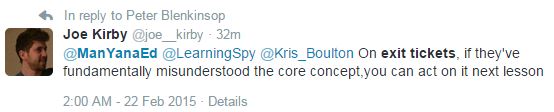

Joe made a succinct response here, which would be in line with the entire hinge question / AfL paradigm, that of immediate intervention and information for future planning:

I tried to expand on the points being made by Didau about ‘learning’ being invisible in a comment on the blog post, and then thought I might as well write it up here as well. I don’t know how well I’m explaining this, so feel free to say if it’s not making a lot of sense.

*****

It depends on how you define ‘learning.’ By example, if a person can solve a two-step equation in one lesson, exceptionally well, does it two dozen times with a variety of equations, but then cannot do it a week later, or a year later – did they learn it?

If a person at the end of one period of instruction understands that they have to start each new sentence with a capital letter, but then in the next piece of writing they hand in more than half of the sentences don’t start with capitals, did they learn that lesson?

I would argue that, institutionally, we have a pallid definition of what it is to ‘learn’ something.

What Didau’s doing is ascribing to the idea that ‘learning is a change in the state of long-term memory; if nothing has been changed, nothing has been learnt.’

See: Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work

.

Now there is obviously a continuum here. The person who could solve two-step equations in one lesson, but not later, clearly has experience that someone else who has never even seen a two-step equation does not have. And from the second example, well perhaps previously they weren’t starting any sentences with a capital letter, so now they’re just in need of practice and feedback to get it up to 100%.

This is well explained by Bjork’s model of each memory having an associated retrieval and storage strength. The storage strength is the thing we are developing over time, whereas it is the retrieval strength only that we can directly measure. It is also for this reason that we have no intuitive sense of storage strength; the only thing we ever observe is a memory being retrieved.

Retrieval strength at the end of a lesson might be very high, since the idea was encountered just moments ago. The person learning is successful in whatever related task they are given (solve an equation, write a paragraph.) But, without storage strength to ‘prop up’ that retrieval strength it quickly falls away:

In this model, ‘learning’ is equated with ‘storage strength.’ Since, according to Bjork, storage strength never diminishes with time (where retrieval strength does), at its apex something is ‘learnt’ if and only if storage strength has become so high that retrieval strength will effectively always be high enough to facilitate immediate recall.

On to your question about exit tickets then. Exit tickets can check, to some extent, whether an idea has been understood in the moment. Can the person solve an equation? Without further prompting, do they get that each of those four sentences needs a capital letter at the start?

What exit tickets cannot check is whether that same person can still recall that next year, or a week later, or tomorrow even.

They do the job of assessing you passed ‘stage 1’ if you will: ‘Form correct memory.’

After that, it is the job of curriculum design to ensure that further ‘learning’ takes place i.e. the development of that memory’s storage strength over time.

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

Thanks for this clarification Kris – that sums up a good deal of my thinking. What I’d want to add is the concept of liminality.

If we say there are, broadly speaking, three distinct states on a students’ journey from not knowing to knowing this might be helpful:

1. Not knowing. At this point nothing relevant has been stored and so nothing can be retrieved.

2. Liminality. Students have begun to lay down relevant knowledge in long-term memory but it is weakly integrated with prior knowledge and so poorly stored. In order to cope with the confusion of “kind of” knowing something students often mimic what they think their teachers want them to do. This leads to a sort of ‘cargo cult understanding’ where you get the superficial aspects but have no idea what’s happening beneath the surface.

3. Knowing. At this point, new knowledge has been securely integrated within existing webs of prior knowledge and students have made it part of their ‘working vocabulary’. They understand the deeper aspects of the new knowledge and can therefore apply to a range of situations which leads to even better storage.

Joe’s right to say that an Exit Ticket can spot complete misunderstandings but I still think that’s potentially misleading and counter productive. If we use AfL techniques to assess understanding in the lesson we are likely to find evidence of mimicry. Some students will be able to mimic well, others won’t but no one will have understood a difficult new concept at a deep level. We should assume that everyone, regardless of what the Exit Ticket says, is in a liminal state and design our schemes of work to make use of what we know about building students’ capacity for retention and transfer rather than getting sidetracked by techniques which merely reveal current performance.

Does that make sense?

Makes perfect sense to me! Thanks for adding that David.

So is it possible to create exit tickets to check for the level of misunderstanding learners currently have?

I feel like you could do it to identify specific misconceptions… but how do we even categorise ‘level of misunderstanding’… ?

Complicated stuff this learning thing. But nice to ponder which this exchange gas certainly done for me. Thanks.

I think ‘gas’ was meant to be ‘has’!!!

I think the problem arises when people read too much into correct exit tickets. They think

Correct exit tickets = green light, plough on ahead = GO GO GO, curriculum coverage, move on move on

Incorrect exit tickets = red light = stop and reteach

The response to incorrect exit tickets is probably accurate, but the response to correct exit tickets *should* be more like

Correct exit tickets = amber flashing light, proceed with caution = do proceed, but be sceptical of whether this one data point is reliable, don’t speed on too fast, don’t let this fool you into doing too little practice or consolidation

Good way of putting it. That probably is a classic mistake in teaching.

You just described my first term in teaching.

Term 4 for me I think – at least, there was a visceral and formative experience I vividly recall.

Incorrect exit ticket should also result in a more cautious approach: “OK, you don’t know it yet. That’s fine – we’ll revisit next lesson, let’s see if you’ve moved on by then.” Because you know what? Sometimes they ‘get it’ without (maybe despite?) our direct interventions.

Pingback: While looking for something else…: Items to Share; 22 February 2015 | The Echo Chamber

This is a very clear explanation, Kris, and a nice addition in the comments from David about liminality (sounds quite Piagetian – doesn’t it? Assimilation/accommodation?) I think the point I would make is an agreement with something that’s in the post – the value in an exit ticket (or any other assessment within an individual lesson or bit of a lesson) is that it helps you to know whether students can do it, or get it, NOW, or not. I think maybe there are three outcomes for lesson planning: none of them can do it – teach it again; they can all do it – move on but remember to provide spaced retrieval, opportunities to practice and/or check again later; they can sort of do it – come back to it but don’t assume you need to start again from scratch (David’s last comment).

Having said that, I still think that this is a bit subject-specific. I remember a Dylan Wiliam example was something like “Explain why a probability can never be more than 1”. Now, you can certainly demonstrate to an observer that if you repeatedly state during a lesson that “A probability of 1 means something will happen every time and it can’t be more likley than that”, students will be able to parrot this back at the end, and I would completely agree with David that this doesn’t tell anyone anything about learning. On the other hand, if you haven’t staged this question then I think answers would tell you something about understanding of what a probability is – maybe not how permanent that understanding is but certainly something useful. Equally, I think that if you are doing a chemistry lesson on the salts produced in neutralisation reactions, and your exit ticket uses a combination of acid and base that hasn’t been in the lesson, then a correct answer strongly suggests they’ve seen the pattern and can apply it, for now. I think in English maybe these sorts of examples are harder to think of and also the subject is more of a whole thing. It’s not very good evidence but the GCSE Core Content for English is 2 pages, Maths is 8, and Science is something like 13 pages per GCSE. Learning about current in circuits is almost completely separate to water waves or Newton’s Laws. The opportunity cost of re-teaching is therefore massive and exit tickets can help with these difficut decisions.

I’ve heard Tim Oates say something similar, name that assessment should happen in a context other than that which was studied. So if studying metamorphosis in tadpoles, you might then ask a question instead about caterpillars.

But… I don’t know. My intuition is that the underlying abstract idea would *not* be understood so immediately; that you could almost guarantee that if you switched contexts there would be immediate failure for the vast majority. I’m always keen to avoid setting expectations too low when keeping this in mind, but it relates to the inflexible/flexible knowledge continuum set out here by Willingham:

Click to access HowDoWeLearn.pdf

If we should expect knowledge to start as being inflexible, then when is it appropriate to start testing for flexibility?

Pingback: Math(s) Teachers at Play – 83rd Edition | cavmaths

I guess how much you can change the context has to be based on experience to some extent. If doing balanced/unbalanced forces then a car is a different context to a skier. For neutralisation reactions, hydrochloric acid + sodium hydroxide is different from sulphuric acid + potassium hydroxide. Are they too different? Are they different enough? That’s a judgement that depends on how much progress you are expecting – for some groups it’s too much, for others it’s too easy to be any more than a formality. Only longer tests can assess across the full range and we should be using them too, but if we can reasonably judge the right level for a LO then we ought to be able to judge the right level for an exit ticket. It’s an opportunity to ask one question from that longer test at the moment when you are planning the next lesson.

Pingback: (Trying to apply) Spacing in Science | mrbenney